“Sarcasm,” Thomas Carlyle wrote, “I now see to be, in general, the language of the devil for which reason I have long since as good as renounced it.” What did he mean by this?🧵

These words will puzzle many who think sarcasm is the ultimate expression of cleverness. They might conclude he’s attacking cheek, wit, banter, teasing, comic relief, gallows humor—all of which are good and make life colorful and worth living.

But he’s not attacking those; sarcasm is something else. What makes this a tricky subject is that Americans have been trained for several decades to be sarcastic, and an attack against sarcasm will seem personal to many.

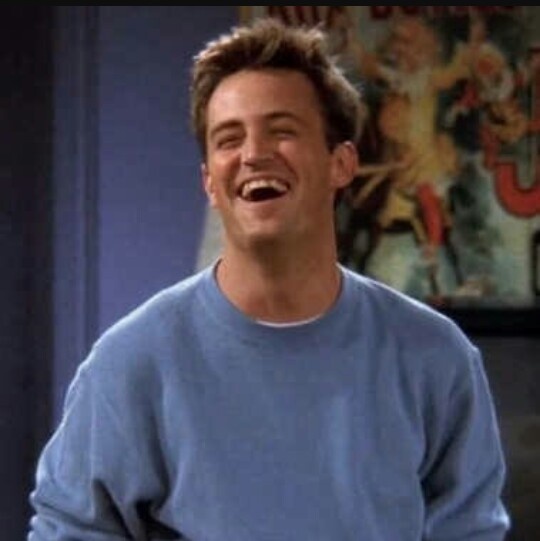

Thanks to our sitcoms, it’s basically a reflexive response—the Chandler Bing Syndrome. Chandler taught the sarcastic mode of being to millions. (I include myself in that; I struggle against my own sarcastic tendencies and training.)

We need a definition which distinguishes basic sarcasm from the more general category of irony, satire, and other things that usually get associated with it. Cambridge defines it thus:

The first part is key: saying the opposite of what you mean, while implying with your tone that you didn't mean it.

Sarcasm is captured to those junior high exchanges in which someone asks an obvious question and has it thrown back in his face: "Are you going to JT’s party?" "Nooo, I’m going to be a total loser and stay home."

As for that part in the definition about being “humorous,” I am unconvinced. Most sarcasm is cheap and easy and pretty unfunny. Nothing small-souled is all that funny; real humor requires a little more touch than that.

And the part about “hurt[ing] someone’s feelings” points to the etymology: sarcasm traces back to the Greek sarkazein "to speak bitterly, sneer," literally "to strip off the flesh.” It tends toward making someone feel stupid.

“The essence of sarcasm,” Henry Fowler says, “is the intention of giving pain by (ironical or other) bitter words.” The true sarcastic is always ready to pounce on others for a naive or silly statement—thus showing their own superiority.

But there’s usually little superiority to display. You pretty much just say the opposite of what you mean, with some snark in your tone.

If sarcasm misses the target—being nasty and self-impressed—frankness hits it. Frankness is about saying what you mean. You don’t blurt out things that don’t need to be said, but when you speak your words convey truth. They reflect reality. https://x.com/ChivalryGuild/st...

The surprising thing for those suffering from Bing Syndrome is that truth is almost always funnier than snark. Some creativity is required, but it’s in frankness that playfulness and humor and manly good cheer can come through. Turning to some examples ...

I get the impression that some would call Stelios “sarcastic” for his response to the Persian who threatened to blot out the sun with their arrows. But his joke is not at all sarcastic; he means what he says, taking the premise of the Persian’s threat and running with it.

The Spartans will fight in the shade and against overwhelming odds, and will do so gladly. His words convey the playful machismo of a man of the sword, but no sarcasm.

Just a little later in the same movie, Leonidas cracks a joke with a similar tone. Call it what you will—dark, funny, true, witty, manly—but it’s not sarcastic. Leonidas is speaking truth: the Spartan culture is war. https://x.com/ChivalryGuild/st...

Another iconic examples comes also from 00s cinema, as Brad Pitt’s Achilles is warned by a young boy in Troy about the size of the man awaiting him in combat. When the boy says he would not want to fight such a large man, Achilles’ reply is pointed, as the truth often is.

Only the brave deserve to be remembered. It is what the boy needs to hear—perhaps it will rouse his soul. This is far superior to an uncreative and sarcastic response like “I’m soooo scared” or “I literally just pissed my pants.”

Compare the manly and unsarcastic expressions above to one from Chandler Bing: Phoebe [explaining why her boyfriend cannot attend an event]: “He’s skating tonight at the Garden. He’s in the ‘capades.” Joey: “The ice capades?” Chandler: “No, the gravel capades.”

Of the lines listed, Chandler’s is the least funny. Sarcasm befits an affluent urbanite like Chandler who works in “statistical analysis and data reconfiguration” and spends much of his life in fashionable coffee shops.

One might even sympathize with Chandler’ tendency, considering the damage inflicted by his libertine parents: sarcasm is his defense mechanism against a world that bloodied him up at a young age. But why would we want to emulate a traumatized boy?

There’s even a sarcastic comment in LotR, voiced by one of the most despicable characters. When realizing on the march to Isengard that they are doomed—about to be annihilated by Éomer’s cavalry—one Orc congratulates another on his “fine leadership.”

“I hope the great Uglúk will lead us out again,” he adds, obviously meaning the opposite of what he says. This is how Orcs talk.

Perhaps there may be cases in which people can pull sarcasm off. Or perhaps some might argue that this age of absurdity requires sarcasm. I’m open to listening to that argument.

But in our personal dealings sarcasm should be used rarely and carefully—or not at all. The point is that our words ought to mean something, and we ought not say things that aren’t true, even if it’s clear we don’t mean them. That’s not what words are for.